— The Guardian: Thursday 5th, November 2015

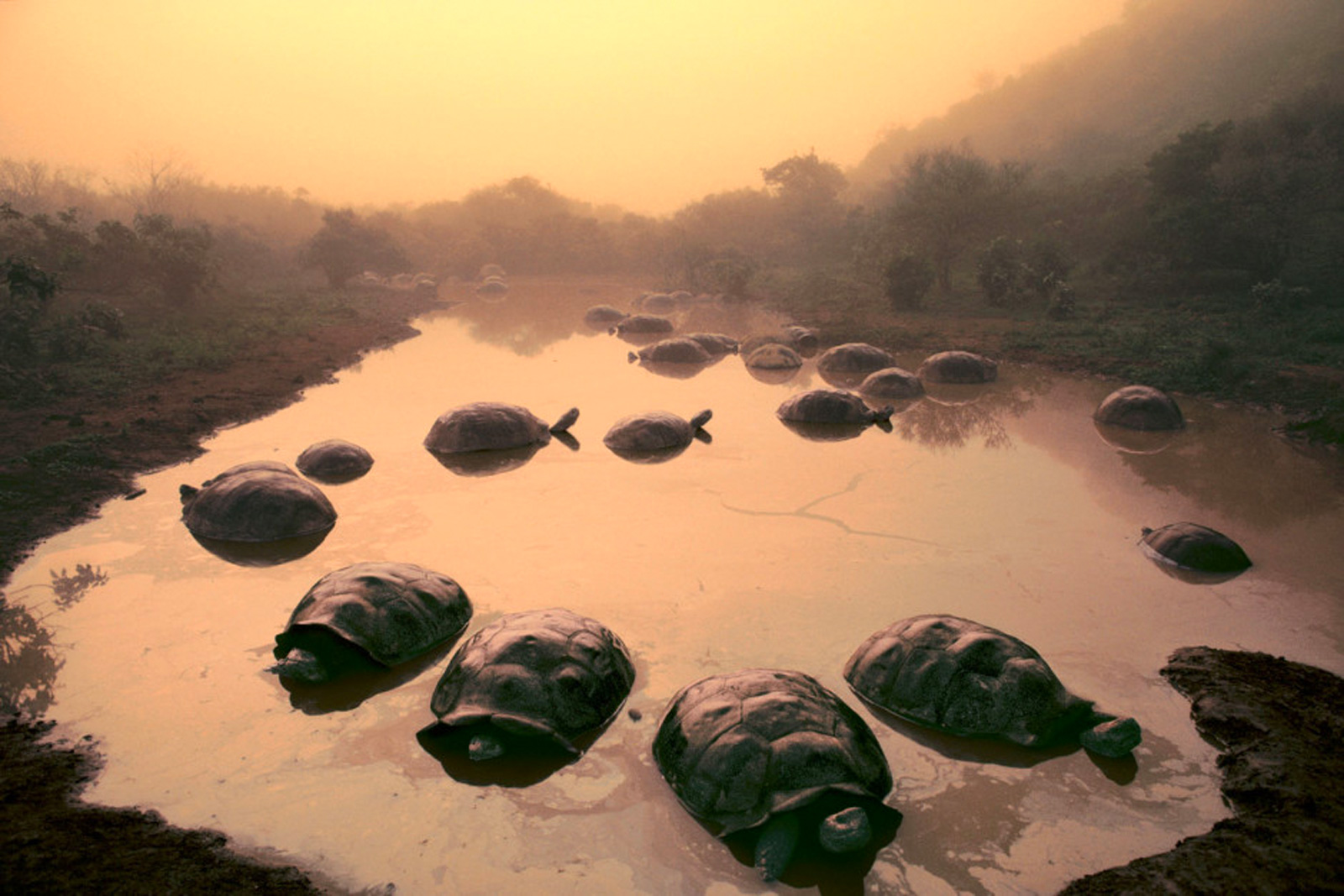

Life started with the humble horseshoe crab. Not life itself, but LIFE: A Journey Through Time, nature photographer Frans Lanting’s multi-year experiment traveling the globe, searching for places and specimens as old as the planet itself. The idea came to him when he was on assignment photographing the horseshoe crabs that gather every spring in a place as prosaic as the New Jersey shore. He realized the scene must have looked much the same eons ago.

Lanting’s big bang came in 2006 with a book, a documentary, a TED Talk and a Philip Glass symphony all dedicated to the ever-changing peripatetic photo show. Now the project has culminated with an exhibition at Los Angeles’s Annenberg Space for Photography, with added video elements and regular screenings of the documentary, which features interviews with biologists including Harvard professor Andrew Knoll.

Once Lanting arrived at the idea for LIFE, he consulted with a list of experts to find the best places and creatures to represent Earth as it appeared in Precambrian times, then went off and photographed them, usually with partner and editor, Christine Eckstrom. “It was a preposterous idea that you could capture this colossal story through still photographs. And for the first couple of years I wasn’t quite sure it would ever reach critical mass,” says Lanting, who spent seven years from that springtime on the Jersey beach with the horseshoe crabs. He visited Haleakala in Hawaii during a volcanic eruption, forests in Botswana, ice formations in Greenland, and learned that Shark Bay, a remote lagoon in western Australia, was one of the few places in the world where stromatolites still exist.

Three billion years old, these amorphous communities of cyanobacteria are credited with releasing the first oxygen into the air, turning the reddish atmosphere of the planet’s earliest days into the rich blue sky we know today. But while it is a rare species and a vital link in the story of life, it isn’t very interesting to look at.

“It took about 10 days until I figured out some ideas,” says Lanting about the unphotogenic colonies which look like large, smooth rocks. “It’s the light but it’s interaction with the subject. I can come up with all kinds of ideas that are based on research and talking with specialists and translate the information into a visual concept that sometimes works. Just as often, I arrive on location and say tear that up and better come up with something new.”

What he came up with was a dawn shot, with tufted pink clouds at the top of the frame mimicking the textured, darker-shaded stromatolites in the foreground. The blue water surrounding them encroaches on the sky, a harbinger of the atmospheric evolution to come.

“The science is the bedrock upon which I built the ideas and ultimately the images,” explains Lanting. “But scientists are their own worst enemy. They know too much. They express themselves though facts and figures. But the general public is much more interested in emotions. We need to go beyond the academic ways of expressing things.”

While Dr Knoll has never heard of one scientist criticizing another for knowing too much, he concedes that most of his colleagues have difficulty expressing fascinating subjects in resonant ways. “People are going to respond to this in a very different way than they do to an article in Scientific American. But I wonder to what extent they take away from it some version of the science story.”

Originally from Rotterdam, Lanting received a master’s degree in economics before moving to the US to study environmental planning. A European in the wild west for the first time, he naturally brought a camera, which changed everything. By the time he was 30, he had settled in Santa Cruz, California, and was on his way to becoming one of the most decorated nature photographers of our time. Most of his work has been carried out for National Geographic, along with other magazines such as Audubon and Life. Winner of numerous prizes, including the 1997 Ansel Adams Award for Conservation Photography, he was made Knight in the Royal Order of the Golden Ark in the Netherlands in 2001.

As artist in residence at Genentech Corporation, a biotech pharmaceutical company in San Francisco, he worked with their imaging staff to find common patterns in the inner workings of the human body and the surface of the planet. The results include photo slides of human tissue, estuaries of blood vessels, cross sections of brain juxtaposed with aerial shots of river estuaries and other natural formations. The idea is to illustrate that we are not separate from nature but part of it. It is why Lanting avoided using “nature” in the title, reasoning that most people think of it as a place to go to on weekends, a place outside of them. The same cannot be said of “life”.

“I feel that we are living in a unique moment in time when we need to transcend the ways we think about nature,” offers Lanting. “We are shaping the future of our living planet. Climate change is just one of the manifestations. I wanted to replace the concept of nature with a sense of life. We are part of this story.”

LIFE is at Annenberg Space for Photography, Los Angeles, until 20 March 2016. Details here.